In the context of almost total national isolation after 1804, the Haitian peasantry has had to call on its own resources for the development of folk institutions and theories to handle the gamut of problems that confront all human societies.' The economic and social isolation which has characterized, and to a degree still characterizes, Haiti as a national unit has meant, among other things, that the rural populace has remained outside of the currents of modern medicine.

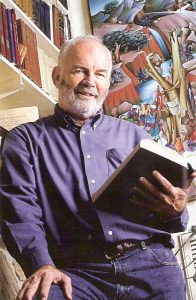

THE GERALD MURRAY ARCHIVE

THE GERALD MURRAY ARCHIVE

Long considered as a reference in regards to anthropological research in Haiti, Gerald Murray’s work, particularly in regards to Agrarian, Ritual and Healing systems of rural Haiti, as well as agroforestry systems and ultimately the relation between people and trees are of utmost importance to anyone wishing to understand the country and its people.

EKO HAITI is thrilled to be able to provide open access to the works, published and unpublished, of American Anthropologist Gerald Murray. The work presented here focuses primarily on agrarian communities, their land tenure, land use, market systems and agroforestry but also deals heavily with the local Afro-Caribbean religious system (“Voodoo” or “Vodou”) and with the evolution of the folk-healing system so closely linked to the ritual system.

We have devised the following descriptive definition: a rural Third World survey is the careful collection, tabulation, and analysis of wild guesses, half-truths, and outright lies meticulously recorded by gullible outsiders during interviews with suspicious, intimidated, but outwardly compliant villagers. The definition is meant to be a caricature not of the villager, but of the researcher; not of all village surveys, but certainly of many.

For several decades anthropologists working in the Caribbean have been explicitly aware of the need to look beyond the confines of the communities which they study, to take into consideration major national and supranational forces which have shaped and influenced local life (e.g. Smith 1956: chap. 8; Steward 1956:6-7; Padilla 1960:22; Manners 1960:80-82). But at first glance, the situation of the people of rural Haiti appears to be somewhat exceptional in this regard.

The following pages will briefly sum up and analyze the information relevant to family planning gleaned in several months of fieldwork in a Haitian hamlet. This period of exploratory research has been a useful preliminary not only for settling in learning the language and becoming acquainted with and acceptable to the members of the research community but also for isolating and clarifying the genuine issues around which the success of a program of voluntary fertility control will ultimately hinge. These issues, which should be the object of more exact study, are by no means self-evident.